|

|

|

|

Graziosi posted on October 30, 2024 14:32

We (Rachael Edwards and Dylan Kneale) would like your feedback on a new co-produced model for child health to enhance its accessibility and value. It depicts the factors thought to impact healthy eating, physical activity, and mental health among young people. We hope that this model can support the development of holistic public health policies and programmes relating to schools.

Our team at the London Alliance for the Co-production of Evidence Synthesis (LACES) have co-produced a model for child health alongside co-researchers with a range of expertise. This model is a type of theory that depicts the factors thought to impact healthy eating, physical activity, and mental health among young people. The model is focused on schools and is designed to support public health decision makers.

We would greatly appreciate you feedback on the model to enhance its accessibility and value. You can access the model here and provide your comments through the link below.

Why did we develop this logic model?

Healthy eating, physical activity, and mental health are complex challenges driven by multiple factors interacting at different levels. An understanding of this complexity is necessary to support public health decision makers in commissioning interventions, and researchers to improve this research. Schools are potentially vital sites for intervening and improving children’s health, and this model helps us to think about which factors may influence a school’s capacity to influence children’s health.

We hope that this model can support the development of holistic public health policies and programmes relating to schools. Although it is likely to be of use to many decision makers, we designed the model with local authority public health teams in mind. The model could help decision makers consider a range of questions including:

- What are the different channels through which policies and programmes can support child health in schools?

- How might the impact of a school health policy or programme vary across children from different backgrounds and with different life experiences?

- What factors might enable or limit the effectiveness of a school health policy or programme?

How did we develop this model?

EPPI Centre researchers and public co-producers with relevant lived/living experience (including parents, teachers, researchers, and young people) previously developed a logic model for child health. We recently worked as a smaller group of co-producers to further refine the model. This smaller co-production team retained a diversity of perspectives – public health researchers, parents, and educational researchers – although we are now seeking more input on this model from a wider group of people.

How you can help!

Now it’s your turn! We’d like your feedback on the model. We want to hear from anyone who could use and/or benefit from the model including local authority public health staff, nutritionists, teachers, and young adults with lived/living experience of issues around healthy eating, physical activity or mental health. We’re particularly interested in the following questions, but any feedback is welcome:

- Which factors are missing?

- Which factors need a better description?

- How holistic is the model?

- How accessible is the model?

Click here to see the model and provide your comments through the link below:

- Please do not include identifying information in your comments

- You must be at least 18 to provide feedback

- Your comments won’t be visible to anyone apart from the research team

- Please contact embeddedresearchers@ucl.ac.uk if you have any questions about the research

Please feedback by November 12.

Click here to provide feedback.

Privacy Notice: The controller for the feedback collected here will be University College London (UCL). Your comments are not being used as research data, but rather as general feedback to improve our logic model. By leaving a comment you are consenting to having your feedback considered by our research team. Your comments will be stored on a secure UCL Teams page for up to ten years. Please contact data-protection@ucl.ac.uk for any questions regarding storage or protection of the feedback.

|

Graziosi posted on September 07, 2024 08:35

We are genuinely excited to announce that as of September 7, 2024, the source code of EPPI Reviewer is now public. It is released under the license called "Functional Source License, Version 1.1, MIT Future License" (FSL-1.1-MIT), which means it can be treated as Open Source (MIT License) for non commercial purposes.

The history of the source code of EPPI Reviewer as it appears today started in 2008 when the first lines of code for what will become EPPI Reviewer 4 were written. EPPI Reviewer 4 became available to the general public in 2010 and very much ever since, we wanted to release its source code. 14 years later, we finally did.

Why release the source code?

The main reason is simple: we want to maximise the usefulness of what we do. Allowing colleagues and researchers from anywhere in the world to look at how EPPI Reviewer works can be useful in a number of ways, many of which we (at the EPPI Centre) can't even imagine, so it has been in our list of wishes pretty much forever.

Relatively recently, another important reason has emerged too, summarised by a single word: "Sustainability". What would happen if the EPPI Centre were to close abruptly for whichever reason? (We don’t expect or plan for this, but we need to think from the users’ perspective!) EPPI Reviewer users everywhere would be stranded, without their data and without a way to recover it or continue working on it. Releasing the source code isn't the full solution to this scenario, but it's a crucial part thereof. It ensures people around the world can pick up from where we "left", in the unlikely scenario whereby we did "leave" (no, we have no reason to believe this scenario is likely!). This additional reason has emerged relatively recently and gradually, as our user-base keeps increasing steadily.

More in general, and perhaps more importantly, we do think that sustainability doesn't pair well with secrecy, one can choose to privilege one or the other, but not both. For a more general (and gentle) introduction to the relation between Open Source practices and sustainability, a good starting point is this article by Amanda Brock.

What took us so long?

The short answer is: we're a small team and want our work to be immediately useful. Doing what was needed to release the source code took weeks of work, during which we didn't make EPPI Reviewer better, so, for us to "find" those weeks, we needed our motivations to grow accordingly. Moreover, besides purely technical issues that needed to be overcome, we also needed to solve a number of other problems.

Competition/sustainability

When EPPI Reviewer 4 was launched, we had no idea whether it would be self-sustaining financially. Would it generate enough income to pay for our salaries and the hardware it ran on? We didn't know. As time passed, we found out it did, although UCL and research grants also contribute. Similarly, right now, we do not know if releasing our source code will mean the crucial source of income represented by user fees will be affected. In principle, once they have the source code, any third party could relatively easily setup an "EPPI Reviewer Plus" enterprise and become a direct competitor. Thus, we know a risk exists, and we need to account for it.

Small team

As mentioned above, merely finding the time to overcome the technical obstacles (which we won't discuss here) is a significant problem for a small team. Besides this, making a project open-source can mean opening it up to external contributors, and this generates more work as aspiring contributors will seek help in understanding the code-base and then their contributions in the form of changes to the source code would need to be tested and quality-assessed thoroughly.

The source code is in different places

This is perhaps the most obvious and easier to understand "technical obstacle": our source code lives in three different "places". Two separate "source code repositories" (one for the core of EPPI Reviewer, one for EPPI Mapper) and then also the Azure Machine Learning environment (and Azure DevOps), where the code running (our increasing range of) Machine Learning tasks lives and runs.

Overall, we needed to figure out how to solve or manage all these problems, and thus it took us 14 years to move from "wish" to "fact".

What did we do?

From 7 September 2024, the source code for the core of EPPI Reviewer is now available as a Public Repository on GitHub. This includes EPPI Reviewer 4, EPPI Reviewer 6, the Account Manager, EPPI Visualiser and more.

With reference to the problems listed above:

We are releasing the source code under a relatively new license called "Functional Source License, Version 1.1, MIT Future License" (FSL-1.1-MIT). This allows the license to cover the source code in one of two ways, depending on the purpose(s) for which it is used. If such purposes are commercial and include competing directly against EPPI Reviewer, then the source code is available (anyone can read it and perhaps obtain insights) but not open (using the code for such purposes is prohibited). Otherwise, the software is covered by the MIT license, which is extremely permissive and solidly fits in all mainstream definitions of "Open/Free Software". Moreover, once the code is 2 years old or older it becomes automatically covered by the same MIT license.

What this means in practice:

- If you want to use the open source for research, educational, not-for-profit purposes, you can/should consider the source code we're releasing as covered by the MIT license, and thus consider and treat it as Open Source.

- If you want to use the same code to create a commercial clone (or partial clone) of EPPI Reviewer, then no, the license that covers the code does not allow you to do so until the 2 year time period after release has elapsed.

- We may revise this licensing decision later on, as we learn more about the risks involved, and/or if we're lucky enough to find different long-term sources of funding.

When it comes to managing possible contributions from 3rd parties, we must admit that our core team is too small and our to-do list is too long, so as a general rule, we will not accept "pull requests" (the technical way by which any 3rd party can send us proposed code changes). Should anyone want to collaborate by contributing to the core codebase, they should get in touch with us instead, and we'll discuss each case individually.

For the time being, the released source code covers the vast majority of EPPI Reviewer – the core source code - meaning that EPPI Mapper and the code that runs in the Azure Machine Learning environment is not yet included. We will also release these at a later date once security issues are ironed out. (The machine learning code contains all kinds of ‘secrets’ to allow it access to storage and other Azure services.) We did not want to let the perfect get in the way of the useful, so we decided to go ahead and release what we can, and will release more as soon as we can. (Certainly in less than another 14 years!)

Concluding remarks

Releasing the source code of EPPI Reviewer feels like a major milestone to all of us and we are extremely excited that we finally managed to. Sure, this is does come with some important caveats and isn't all of the code that runs EPPI Reviewer, but on the other hand, it's the result of 16 years (and more, as the origins of EPPI Reviewer actually trace back to the early nighties) of dedicated work of us here in the EPPI Reviewer team, so it does feel like a very important (if not final) step.

Should anyone wish to start trying to make sense of all this code, please do not hesitate to get in touch via EPPISupport - you will then be put in touch with the developers who will try their best to point you in the right direction(s).

|

Graziosi posted on July 26, 2024 10:30

Interactive evidence maps help support the use of research evidence in practice and policy-making through their visual appearance, to show what is available and where gaps exist. Design is a key element. What are the options and issues to consider when creating one? Claire Stansfield and Helen Burchett reflect on their experiences from developing two maps on digital interventions for alcohol and drug misuse (1).

Why create an interactive evidence map?

Interactive evidence maps provide a visual overview of a collection of evidence and enable users to explore the content at varying levels of detail. They are useful to describe the nature of research or interventions (such as population focus, study design, setting), and by doing so also illustrate gaps. They can be particularly useful for seeing at a glance, what exists or is lacking, across a broad topic area. Digital alcohol and drug interventions are an example of such a broad area. For our project we produced two maps, which are contrasting examples of the purposes and the level of details of maps.

One map contains 1,250 primary research citation records of research evaluations and gives a visual overview of what intervention evaluations had been conducted, with options for filtering the map view, but providing only the citation details for each individual record. In contrast, our second map of intervention practice and systematic reviews, includes just 58 records, and fewer options for filtering the map view, but it contains a detailed descriptions within each record. Although evidence maps normally focus only on research evidence, this map describes 40 interventions available for use in England, alongside 18 internationally-focused systematic reviews. We highlight three key considerations in developing the maps.

1) Developing an organising framework

Developing a structure for organising the map was of fundamental importance to categorise the records and guide users. A street-map shows transport networks, road systems, footpaths, and there are conventions and expectations around using and navigating this type of map. Interactive evidence maps take a variety of forms and users may not be familiar with using them. A map needs at least two elements (one for rows and one for columns), and a third element is an option for segmenting records at each row and column intersection. Each element should be defined carefully and applied consistently to ensure integrity of the maps.

The final organising framework for our maps was derived from discussions with the maps’ commissioners, the former Public Health England. The rows in the maps distinguish between interventions directed at drug and alcohol misuse. A third row contains both interventions directed at drugs and alcohol and those where it was unclear as they were generically targeted to ‘substance misuse’. The columns separate the intervention purpose of prevention, treatment or recovery from alcohol or drug misuse. Though other options considered were the underlying intervention strategy used (e.g. tracking or feedback, cognitive therapy), and the digital nature of the intervention (e.g. smartphone app, videoconference call). For the second map, interventions in practice and systematic reviews were separated and the systematic reviews were segmented into three quality ratings.

2) Striking a balance between a broad view and detail

The level of detail in the maps was another consideration. For example, should drugs be grouped as one, or should there be separate rows for each drug? We grouped the drugs together, as separating them seemed to create a level of detail that would prevent the user from gaining an ‘at-a-glance’ sense of the landscape. However the primary research map allows filtering to show only those that relate to specific drugs, and both maps allow searching within records for a drug name. The map of primary studies also has options to filter the visual overview on study measures (outcomes, process, cost, other), publication year and geographical location, which helps in navigating a diverse collection of records.

For the map of intervention practice and systematic reviews, we produced detailed descriptions about each record. For the systematic reviews we extracted pertinent findings and also summarised their population and focus.

Copyright issues prevented displaying abstracts in the primary research map; they are displayed in the second map where permitted.

3) Enhancing usability

The appearance and usability of the map is fundamental to its appeal and use. Although the maps initially requires a little familiarisation, we tried to make them as straightforward as we could. We piloted them with stakeholders and colleagues, which provided useful feedback.

The labels describing each element need to be clear and concise to the user, and an accompanying glossary helps explain the labels.

We used the EPPI-Mapper tool, which integrates with EPPI-Reviewer review management software via a json file type (it is also possible to create a simple map without an EPPI-Reviewer account using an EndNote RIS file) (2). While underlying functions are fixed by the tool, there was flexibility to adapt the maps to our own needs.

We created tabs along the top of the maps’ webpages to summarise the methods used to produce the maps, display the glossary, and provide guidance on using the map.

Final reflections

The process of developing the map involved multiple iterations, ensuring that both the content and appearance are credible, consistent and usable. It was particularly time-consuming to prepare and finalise the bespoke descriptions for the second map. EPPI-Mapper has acquired additional functionalities since we produced these maps, including improved functionality for adding summaries.

Going forward

There are different approaches to developing maps to visually represent research in broad topic areas. Our two maps show two distinct but complementary uses of the mapping tool. When developing maps, decisions are needed on organising the content, the level of detail to convey and how it is provided (e.g. filters or segments). Usability needs to be considered through choice of labels, colours, supplementary content and user instructions.

You are welcome to share your thoughts on using and creating maps via the comments option below.

About the authors

Claire Stansfield is a Senior Research Fellow at EPPI Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, who focuses on information science for systematic reviews and evidence use support.

Helen Burchett is an Associate Professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She has been working on public health/health policy systematic reviews for over 20 years.

Bibliography

- Digital interventions in alcohol and drug prevention, treatment and recovery: Systematic maps of research and available interventions [Internet]. Available from: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3879

- Digital Solution Foundry, EPPI Centre. EPPI-Mapper [Internet]. EPPI Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London, UK; 2023. Available from: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3790

|

GillS posted on December 21, 2023 14:54

Well, the year seems to have flown by once again for us here at the EPPI Centre. Possibly because we have been super busy immersing ourselves in all things systematic review-related. Here is a round-up of the highlights of our year!

Shiny EPPI people!

This year we have welcomed two new team members and the return of a former EPPI colleague!

- Silvy Matthew joined the team for our new Evidence Synthesis Group (see below for details) – working across projects on screening for diabetic eye and on designing evidence synthesis methodology to capture contextual factors in a more helpful way for informing decision-makers.

- Hossein Dehdarirad is an information scientist whose primary interests are information retrieval and management, developing search strategies for evidence synthesis projects, recommender systems, text analysis, machine learning, as well as scientometrics.

- We’re also delighted to welcome back Mel Bond as a Research Fellow after a stint as a Lecturer (Digital Technology Education) at the University of South Australia.

We celebrated two of our team members whose contributions to the EPPI Centre and beyond, were recognised. Gillian Stokes became an Associate Professor of Inclusive Social Research and Rachael Edwards is now a Senior Research Fellow.

We were super-proud of our colleagues James Thomas, Rebecca Rees, Sandy Oliver, Mel Bond and Irene Kwan who were recognised for being in the top 2% of scientists in the world in the Elsevier and Stanford University’s 2023 list of the worlds most cited scholars of their field!

New reviews published in 2023

Work that has been published this year for the London-York NIHR Policy Research Programme Reviews Facility with our partners at the Centre for Research and Dissemination and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, includes:

Please visit the EPPI Centre website for a comprehensive list of published reviews.

New ventures

London Alliance for the Coproduction of Evidence Synthesis (LACES): This year we were excited to launch LACES, which is one of nine Evidence Synthesis Groups funded across the UK by the NIHR. LACES is a collaboration of three UCL centres including the EPPI Centre, the UCL Co-Production collective and the Health Economics Policy Lab. The team will undertake a rolling programme of policy-commissioned reviews during a five-year period. Watch out for publications from LACES in 2024!

Much of our current work has proven to be very topical, such as our growing body of reviews around equity, machine learning and artificial intelligence. We are excited about publications on these topics in the coming year.

Key presentations

We were delighted to welcome the return of the Cochrane Colloquium in 2023, especially as it was on our home turf in London!

Here’s a few of the team’s workshops from this year’s colloquium…

And a few of our presentations…

Looking forward to 2024...

We’re already looking forward to catching up with national and international colleagues in September at the Global Evidence Summit in Prague!

And, we’re also very much looking forward to hosting some exciting presentations at the London Evidence Syntheses and Research Use Seminars which we run with colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). Kicking off the 2024 series on 17th January, will be our very own James Thomas who will be discussing New 'AI' technologies for evidence synthesis: how do they work, and can we trust them? – we hope you can join us for this talk, either in person or online!

We hope that the festive season will be all that you hoped for and that 2024 will bring lots of exciting projects for you too.

Wishing you all a wonderful festive break!

|

Graziosi posted on December 19, 2022 15:02

For research teams everywhere, it seems the last few years since the COVID-19 pandemic began have been exceptionally busy. 2022 has been another very busy year for the EPPI Centre team. Gillian Stokes and Katy Sutcliffe look back over the year and share some of the highlights!

For research teams everywhere, it seems the last few years since the COVID-19 pandemic began have been exceptionally busy. 2022 has been another very busy year for us here at the EPPI Centre. So, we thought we’d look back over the year and share some of our highlights!

Shiny EPPI people!

This year it’s been wonderful to welcome three new team members.

We also celebrated one of our longest serving team members, Rebecca Rees, becoming a Professor of Social Policy and Head of the Social Science Research Unit (SSRU) where the EPPI Centre is based!

New reviews published in 2022

Reviews published this year for the London-York NIHR Policy Research Programme Reviews Facility with our partners at the Centre for Research and Dissemination and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine include:

We’ve also produced a number of reports for the International Public Policy Observatory on COVID-19. Including our most recent review on misinformation in COVID-19.

Please do visit our website for a comprehensive list of published reviews.

New methods work

Handling Complexity in Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of Public Health Interventions (CEPHI): This year we’ve been developing and testing four new methods for synthesizing evidence to better account for context than standard statistical meta-analysis approaches as part of this NIHR funded project. This work was underpinned by coproduction, and supported by the UCL Co-Production collective. Watch out for publications on this in 2023!

Examining the dimensions of equity (Research England Policy Support Fund): We are examining the methods used by systematic reviewers to conceptualise possible dimensions of health equity impacts of public health interventions, such as using a PROGRESS-Plus approach. These dimensions include socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity and gender/sex. We are also looking at the practical and conceptual issues encountered in applying such methods.

Key publications and presentations

We have been busy sharing our knowledge too.

Several team members contributed to and presented at a virtual conference in partnership with Manipal in India: International Conference on indigenizing systematic review evidence to local context for informing policy and practice decisions organized by Manipal College of Nursing, Manipal, Public Health Evidence South Asia, PSPH, MAHE in collaboration with Social Science Research Unit, Social Research Institute, University College London, UK.

We thoroughly enjoyed hosting a hub for the 2022 What Works Global Summit. The EPPI Centre team presented several papers and were delighted that the best session award went to a session on innovative approaches in evidence synthesis, which included three EPPI Centre presentations on the CEPHI project!

Here’s a few of the team’s publications from this year …

Looking forward to 2023 ...

New projects

We have two exciting new projects lined up for 2023!

A new round of funding from the International Public Policy Observatory means we’ll continue to contribute to reviews about the best ways to mitigate social harms associated with COVID-19.

We were also delighted to be successful in our bid to become one of the newly funded National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Evidence Synthesis Groups. We're extremely excited to be drawing on a range of cutting-edge methods to produce reviews during this five-year contract including: Engagement with stakeholders to ensure relevance; Co-production to ensure equity and inclusivity; Evidence-to-decision methods to ensure utility and impact; and Automation and continuous surveillance to ensure up-to-date evidence.

Events

We’re very excited that the 2023 Cochrane Colloquium will be on our home turf in London and hope to catch up with many people there!

And, we’re also very much looking forward to hosting some further excellent seminars as part of the London Evidence Syntheses and Research Use Seminars newly relaunched in collaboration with colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). We’re trialling a hybrid format that we hope means we can connect with reviewers well beyond our London setting. Kicking off the 2023 seminars, will be a seminar on PPI in systematic reviews: challenges and possible solutions? On 25th January – we hope you can join us!

Wishing you all a wonderful festive break!

Image: "christmas tree lights" by pshab is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0..

|

Graziosi posted on September 10, 2021 13:00

The concept of embedding researchers into policy and other settings is gaining traction as a way to enhance the role of research evidence in informing decision-making. A new EPPI Centre project explores the influence that 'embedded researcher' interventions could have in public health decision-making (see project page here). Embedded researcher interventions may be potentially useful in helping public health organisations to become more research active as they are challenged by widening health inequalities from COVID-19 and budget constraints. Early on in the project we have been confronted with a thorny issue – exactly what is an ‘embedded researcher’? In this blog Dylan Kneale, Sarah Lester, Claire Stansfield and James Thomas discuss this challenge and why researching this ‘intervention’ is important, and we are interested in your feedback on this.

By Dylan Kneale, Sarah Lester, Claire Stansfield and James Thomas.

Introduction

Embedding researchers into policy and other settings is thought to be a way of enhancing research capacity within organisations to enable them to become more involved in the research process either as consumers, generators, commissioners, influencers, stakeholders or a mixture of these roles. The literature suggests that research evidence could have a more prominent role in public health decision-making than is currently the case1 2. In our project, we view embedded researchers as potential disruptors of organisational cultures, who can enable organisations to become more active through occupying roles as mobilisers or (co)producers of research, or facilitators of research use. Embedded researchers could address these issues in a number of ways including through (i) actively researching and contributing to decision-making processes; (ii) changing cultures around research engagement, including the indirect or diffuse influence of research (enlightenment), direct research utilisation (instrumental usage), or research generation; and (iii) helping to produce research evidence that matches the need of decision-makers with regards to the research questions asked and their contextual salience. Part of our project involves systematically identifying research evaluations of embedded research across a range of policy, industry and commercial settings in order to produce a systematic map and a systematic review. Developing a set of principles to define an embedded researcher is crucial to this goal, as existing definitions of embedded research do not fully capture what we are seeking to achieve.

Existing definitions of embedded researcher

Embedded researchers within local public health decision-making contexts have previously been defined as those ‘researchers who work inside host organisations as members of staff, while also maintaining an affiliation with an academic institution’3. McGinty and Salokangas (2014)4 define embedded researchers as: “individuals or teams who are either university-based or employed undertaking explicit research roles […] legitimated by staff status or membership with the purpose of identifying and implementing a collaborative research agenda.” Meanwhile they define embedded research as: “a mutually beneficial relationship between academics and their host organizations whether they are public, private or third sector” (McGinity & Salokangas, 2014, p.3). While these definitions are unproblematic in many ways, the extent to which this definition captures the plurality of models of embedded research is unclear, and the extent to which some of the models of placement where researchers may not feel they have, or may not be recognised as having, dual affiliation is unknown. This is of significance for our systematic map and review. For example if applied literally, the first definition may serve to omit forms of embedded research activity undertaken by researchers who may be based in a host (non-academic) organisation but may not be considered ‘staff’ (e.g. PhD students); meanwhile the second definition, if applied literally, could lead to very short term activities such as delivering research training, being in scope. These ambiguities appear to suggest that ‘embedded researcher’ appears as a concept that we may know when we see it, although is challenging to define precisely.

Why is defining an embedded researcher so challenging?

Some of the reasons why defining embedded researchers is so challenging include:

- Terminology: Embedded researchers, researchers-in-residence, seconded researchers, policy-fellows, embedded knowledge mobilisers, and several other terms appear to be aligned with the focus of our project.

- Intervention complexity: While embedded research activities are rarely broken down into intervention ‘components’ per se (an aim of our project), we would nevertheless expect that an embedded researcher intervention would have several interacting ‘components’, with change occurring in non-linear ways that are manifested across different organisational roles and levels, and that there would be a high degree of tailoring across embedded researcher ‘interventions’ 5; these properties are synonymous with intervention complexity.

- Fuzziness: Not only is an ‘embedded researcher’ a fuzzy concept in itself; it is also predicated and defined through a number of other fuzzy concepts (e.g. ‘research-active’, ‘organisational change’, ‘research skills’ etc.) each of which is open to interpretation.

- Patterns of evaluation: Although embedded research activities have a long tradition, our initial assessment of the literature suggests that these interventions tend to be evaluated through self-reflection and descriptive case studies. Although these are useful, richer evaluation data being made available would help to understand impacts of embedded researchers.

- Non-manualised: Related to the points above, embedded research ‘interventions’ tend to take place without any form of ‘manual’ or ‘handbook’ on how the intervention should be conducted.

Towards a set of principles defining embedded research activity

Rather than a crisp neat definition, embedded research activity may instead be more usefully defined through a set of principles. With the input of our steering group, we view embedded researchers as being defined by the following principles:

(i) they enable research activity and research use. For example, they may undertake research, facilitate the conduct of research (through sourcing data, creating data sharing arrangements or advising on research processes), and support research use;

(ii) they are co-located in a defined policy, practice or commercial formal organisation;

(iii) they are situated within a host team (physically or institutionally or affiliation or culturally) and/or are expected to work within the host team culture for a high proportion of their time as a team member working on and solving practical problems;

(iv) they have an affiliation with an academic institution or research organization, or their post is specifically funded by an academic institution or research organization;

(v) these activities entail continued engagement with a host team (i.e., an embedded researcher is more than a notional job title but a different way of working for researchers);

(vi) the relational nature of embedded research necessitates that this is a long-term activity (i.e., unlikely to be possible in less than a month);

(vii) we expect that host organisations will be able to influence and direct the work of embedded researchers (i.e., embedded researcher activities are generally distinct from, for example, an ethnographic study of policy-making in an organization);

(viii) we view embedded researchers as contributing pre-existing skills and experience to the host organization, and not developing these skills on-the-job and therefore we do not view taught degree placements as examples of embedded researcher activities;

finally, and crucially (ix) we view embedded researchers as exemplifying a two-way relationship where there is learning to be gained for both embedded researchers and their host organisations. Our definition also leaves open the possibility of bi-directionality in that researchers could be embedded into policy/practice settings and that those from policy/practice settings could be embedded into research organisations (provided they meet the other principles).

Why is studying embedded researcher activity important?

Embedded researchers may be in a pivotal position to actively span boundaries between policy organisations and research organisations. This may be important as we emerge from a period where Local Authority public health teams are being asked to do more with less, having been besieged by cuts to budgets pre-dating the COVID-19 pandemic6, and where public health systems have been under massive strain during the current pandemic. Our research is also taking place in the context of new proposed changes in health systems and delivery structures with a focus on further integration of public health, ‘clinical’ health (NHS), and social care (among other proposed changes7), and further changes in the organisational structure of public health and the abolishment of Public Health England8, requiring greater consideration of the role of embedded researchers within integrated teams.

As a team we are also interested in whether embedded researcher interventions can help to address an emerging gulf in terms of health inequalities. While our understanding of the extent and nature of health inequalities appears to be increasing, this understanding has generally not (i) mitigated the increasing gap in health outcomes between different social groups; or (ii) kept pace with our understanding of if/how health inequalities can be addressed at the local level. We are interested if embedded researchers help to address these gaps and how.

Why have we written this blog?

If you’ve read this blog to this point – thank you! – and our intention in writing this blog is to reach out to ask for your input in the early days of this project. Please get in touch with us (email D.Kneale@ucl.ac.uk) if you would like to help in any of the following ways:

- Comment! Let us know what you think of our definition of embedded researchers

- Alert us! Let us know if you have any studies that you think should be included in a review of embedded researcher activity, or if you are working on relevant research in this area.

- Get involved! We are currently scoping out an evaluation study of embedded research activity. If you are working as an embedded researcher in public health, or are planning to do so, please let us know. We would love to talk to you about this.

References

1. Kneale D, Rojas-García A, Raine R, et al (2017). The use of evidence in English local public health decision-making. Implementation Science, 12(1):53.

2. Orton L, Lloyd-Williams F, Taylor-Robinson D, et al (2011). The use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: systematic review. PloS One, 6(7):e21704.

3. Vindrola-Padros C, Pape T, Utley M, et al. (2017) The role of embedded research in quality improvement: a narrative review. BMJ Quality and Safety, 26(1):70-80.

4. McGinity R, Salokangas M (2014) Introduction:‘embedded research’as an approach into academia for emerging researchers. Management in Education 28(1):3-5.

5. Thomas J, Petticrew M, Noyes J, et al. (2019) Chapter 17: Intervention complexity. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (2nd ed) Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons.

6. Iacobucci G (2016) Public health—the frontline cuts begin. BMJ, 352.

7. Iacobucci G (2021) Government to reverse Lansley reforms in major NHS shake up: British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

8. Vize R (2020) Controversial from creation to disbanding, via e-cigarettes and alcohol: an obituary of Public Health England. BMJ 371.

|

Graziosi posted on April 12, 2021 12:22

Over the past year we have seen what may euphemistically be described as “ambitious” uses made of predictive modelling to inform public policy. This is not a new phenomenon, but an established direction of travel. Unfortunately, such models have epistemic limitations that no amount of optimism can overcome. Assigning individuals to specific categories – with direct consequences for their lives and without recognising uncertainty in the prediction – is unsupportable scientifically and ethically. It ignores intrinsic uncertainties, reinforces existing structural disadvantage, and is inherently and irredeemably unfair. Model-based predictions may have an important role to play but, despite advancements in technology and data, we still need to exercise great caution when using predictions to place individuals in categories with real-world consequences for people's lives.

By James Thomas and Dylan Kneale

‘Scientific’ prediction is viewed as a necessary precursor for, and often a determinant of, public policy-making (Sarewitz & Pielke Jr, 1999); without some form of prediction or forecasting of the likely impacts of policy decisions, decision-makers may find themselves paralysed by inaction or shooting in the dark. Rather than gazing into crystal balls, decision-makers can draw on an increasingly sophisticated array of data and methods that are used to generate predictions. There is a lot of enthusiasm for these predictions, and some have claimed that they have the skills to forecast future events precisely; that they are ‘super-forecasters’ (Kirkegaard, Taji, & Gerritsen, 2020). However, while new possibilities are indeed opening up, we need to be mindful of the assumptions that underpin statistical models, and of the fact that large datasets and sophisticated statistics cannot perform miracles, simply because they are large and sophisticated. ‘Super-predictors’ are still subject to basic evidential laws that cover all research.

This is a wide-ranging field, although the issues we focus on here mainly reflect the epistemic impossibilities of using model-based predictions indiscriminately to allocate individuals into discrete categories of real-world significance, without acknowledgement of the uncertainty in doing so.

The implication that arises is that, where uncertainty cannot be incorporated in a real-world use scenario, then the use of the model in that scenario is inadvisable and manifestly unethical. This blog is prompted by recent examples in UK educational policy where there have been attempts to extrapolate model-based predictions to allocate individuals into categories, as well as debates in public health suggesting that there is widespread potential for predictions to be used in this way. These are not isolated examples and there are examples across public policy where model-based predictions have been used to make decisions about individual outcomes; for example model-based predictions of recidivism in the US have been used by judges in decisions about whether to release or hold a defendant before trial (Dressel & Farid, 2021)*. The (mis)use of predictive models and algorithms to ‘objectively’ and deterministically categorise individuals into discrete categories of real-world significance leads us to regard such exercises as attempts to escape epistemic gravity with optimism.

Extrapolating predictions to individuals

Models used for prediction purposes are of huge value across several areas of public policy and practice. Some predictions may have reasonable predictive power for groups of people with particular social profiles (e.g. socioeconomically disadvantaged vs advantaged people), but don’t travel well when applied to individuals. This can be problematic for at least six reasons:

The first, most fundamental issue is that predictions are made on the basis of probabilistic/stochastic models, but the classification of individuals into real-world categories is deterministic and crisp. A recent example of the flaws in this reasoning involved the use of predicted grades in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 to estimate children’s academic achievement. When predicting an exam grade based on a regression model, there would be uncertainty around the prediction itself, and the model would include an error term that denoted the unexplained variance. This uncertainty is ignored when the prediction is extrapolated from the model to allocate an individual grade to a real-world person, and the ‘fuzziness’ of the prediction is ignored. This is despite the range of uncertainty when predicting a (new) individual value from a regression model being wider than the range of uncertainty when interpreting a statistical parameter from a model, because of the added uncertainty in predicting a single response compared to a mean response. In the case of A-level and GCSE exams, a more accurate way of presenting results may have been to put intervals reflecting uncertainty in prediction around them. However, this would have resulted in the slightly bizarre situation where someone, for example, might have been predicted and awarded a grade ‘between A and C’. This is clearly not operational in practice, especially as some students could be allocated grades spanning the entirety of grades A-E, but it would have exposed the inherent uncertainty in the model; something that was concealed by the crisp prediction.

Secondly the predictions, and certainly the approaches underlying the creation of the predictions, may not have been developed with the intention of being applied to wide swathes of the population indiscriminately, and to assign individuals to categories of real-world significance. Instead, the logic underlying these models may hold that predictions from models be useful as diagnostic aids, but not the sole determinant of individual classification. If a prediction is to serve as a diagnostic aid, and not the sole basis of individual classification, the prediction may need to be based on, or combined with, additional information about the individual.

The third issue is that even when we have reliable prior information about an individual, using this in a prediction does not reduce error to non-trivial levels. In the case of predicting grades based on previous attainment for example, we are only able to do this with limited accuracy (Anders, Dilnot, Macmillan, & Wyness, 2020). Nevertheless, in the case of last summer’s school grades debacle, models incorporating past achievement at school level were treated as being entirely deterministic, with zero error – not a defensible position. Furthermore, the accumulating evidence demonstrating how poor we are at predicting individual grades undermines the entire idea that predicting individual academic achievement has analytic value, and suggests that the widespread use of individual predictions in the education system is outdated (see twitter thread by Gill Wyness and paper by Anders et al. (2020)).

The fourth issue is that increasingly sophisticated modelling and technologies can engender false confidence in our ability to predict. A recent example involves the concept of Precision Public Health (PPH), the topic of a new report by the EPPI-Centre, which refers to use of novel data sources and/or computer science-driven methods of data analysis to predict risk or outcomes, in order to improve how interventions are targeted or tailored. Our work on PPH suggests that where evidence is generated using new methods of analysis (specifically Artificial Intelligence) and/or new forms of data, that the findings from this evidence have a tendency to be interpreted by others to support claims about improvements in accuracy in ways that overreach the findings in the original study. Alongside this, we also observed that many of the new ways of analysing data and creating predictions about who or where may benefit most from a given Public Health intervention had not been evaluated against performance from more established methods. Certainly in the case of some analytical techniques, there is conflicting evidence around whether new approaches, such as those used in machine learning, can and do outperform traditional analytical methods such as logistic regression in prediction models (Christodoulou et al., 2019).

A fifth issue revolves around measurement error in the variables and other inaccuracies in the composition of the data used to generate the prediction, including missing data. Although these issues represent caveats to most if not all quantitative social science, the implications for model-based predictions may be unexpected.

A sixth issue is the potential for predictions to reinforce existing systemic biases and disadvantages. Returning to the example of school grades, there is a good deal of evidence demonstrating that the final grades that young people achieve in schools reflect systematic disadvantages faced by poorer and minoritised groups (Banerjee, 2016). A ‘perfect’ prediction model would be one able to replicate the exact results of ‘average’ (non-COVID-19) school years, which would include replicating these systemic inequalities and biases. The subsequent use of these models to predict future outcomes for individuals means that inequalities persist and are actually reinforced by prediction models. For instance, with respect to the earlier example of recidivism, a widely used tool to generate model-based predictions of recidivism in the US systematically overestimated the risk of black defendants re-offending and underestimated the risk of re-offending for white defendants (Dressel & Farid, 2021).

Allocation of individuals into discrete, ‘neat’ categories, on the basis of an ‘objective’ model, belies both the fuzziness of models and the structural disadvantages and structural racism that are underlying features of the models. This was one of the concerns also expressed about the direction of travel of Precision Public Health, where predicted differences in health were at risk of being interpreted almost as ‘innate’ and static features of individuals and attributable to individual factors, thereby overlooking structural and systemic disadvantages that give rise to these differences. Using predictions from models that reflect an unequal society, to predict outcomes for individuals, risks perpetuating further inequalities and undermines claims of objectivity, if the underlying model unquestioningly reproduces and perpetuates the subjectivities and biases of society at large, when categorising individuals.

Concluding points

Predicting outcomes for individuals based on population-level models and treating the source models (and the prediction) as having zero error is an epistemic impossibility. Similarly, treating error from a model as constant and fixed over time, contexts, and populations is also clearly problematic and not supported by evidence. However, the issue is often less to do with the robustness of the underlying model, but more a reflection of the mismatch between the underlying model assumptions and the ambition for real-world individual-level applications of the prediction.

Regardless of their ostensible superiority, we should approach even the most sophistically derived predictions for individuals with a critical eye with regards to the issues outlined above. AI-based predictions can sometimes be viewed as authoritative because of the putative improvement in the precision of the prediction, based on the novelty of the data and complexity and perceived objectivity of the algorithms used to generate them. Our own work around PPH emphasised that there is merit in both (i) questioning the rationale for prediction, and (ii) questioning the evidence base supporting the prediction for individuals (Kneale et al., 2020).

Over the year we have seen the phrase ‘following the science’ bandied about by policy-makers, and often directed at the use of predictions of likely scenarios that could follow in terms of the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. The narrative of politicians during the COVID-19 pandemic has been one where model-based predictions, albeit ones directed at a population-level, have been viewed as a form of instrumental evidence to base policy decisions upon. However, because of the degree of uncertainty involved in generating these predictions, they may instead be at their most helpful in further illuminating the landscape within which policy decisions are made, rather than for instrumental use.

In the case of predicted grades, the literature was clear for some time before that predictions of future grades for individuals are far from accurate. The aftermath provides an opportunity to think again about how we use individual predictions in the education system, but perhaps more broadly across policy domains. Fundamentally, we should accept that it is simply impossible to use these models deterministically to allocate individuals to crisp categories with real-world consequences: we cannot overcome epistemic gravity with heroic optimism.

About the authors

James Thomas is professor of social research & policy and deputy director of the EPPI-Centre. His interests include the use of research to inform decision-making and the development of methods, technology and tools to support this.

Dylan Kneale is a Principal Research Fellow at the EPPI-Centre. He is interested in developing methods to enhance the use of evidence in decision-making, focusing on public health, ageing and social exclusion.

Notes and references

*The types of model-based prediction of most concern here are those that involve prediction of a future state or event which may be observed under normal conditions or with the passing of time, and less so those that involve ‘prediction’ of a latent (unobserved) contemporaneous state (which reflect more a form of categorisation than prediction).

Anders, Jake; Dilnot, Catherine; Macmillan, Lindsey & Wyness, Gill. (2020). Grade Expectations: How well can we predict future grades based on past performance? Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities, UCL Institute of Education, University College London.

Banerjee, Pallavi Amitava. (2016). A systematic review of factors linked to poor academic performance of disadvantaged students in science and maths in schools. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1178441.

Christodoulou, Evangelia; Ma, Jie; Collins, Gary S; Steyerberg, Ewout W; Verbakel, Jan Y & Van Calster, Ben. (2019). A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 110, 12-22.

Dressel, Julia & Farid, Hany. (2021). The Dangers of Risk Prediction in the Criminal Justice System. MIT Case Studies in Social and Ethical Responsibilities of Computing.

Kirkegaard, Emil Ole William; Taji, Wael & Gerritsen, Arjen. (2020). Predicting a Pandemic: testing crowd wisdom and expert forecasting amidst the novel COVID-19 outbreak.

Kneale, Dylan; Lorenc, Theo; O'Mara-Eves, Alison; Hong, Quan Nha; Sutcliffe, Katy; Sowden, Amanda & Thomas, James. (2020). Precision public health – A critical review of the opportunities and obstacles. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Research Institute, University College London.

Sarewitz, Daniel, & Pielke Jr, Roger. (1999). Prediction in science and policy. Technology in Society, 21(2), 121-133.

Image source, by Emir ÖZDEMİR, pixabay license.

|

Graziosi posted on October 03, 2018 12:54

EPPI-Reviewer is the software tool developed and used by those at the EPPI-Centre to conduct Systematic Reviews. It is also offered as a service for the wider Evidence Synthesis research community. At the same time, it plays a critical role in enabling methodological innovation. James Thomas and the EPPI-Reviewer team share an insight on their current development priorities as well as the general philosophy that drives their effort.

This is the first in a series of blogs about EPPI-Reviewer. We have many exciting developments in the pipeline and will use this blog to let you know about them over the next few months.

This blog piece sets the scene. It gives a little flavour of the development philosophy behind the software, and some of our current development priorities.

Development philosophy

EPPI-Reviewer grew out of a need within the EPPI-Centre for bespoke software to support its reviewing activity. We have always been interested in methodological innovation and needed a tool that would support this. We also conduct systematic reviews in a wide range of subject areas and using a range of different types of research. We therefore needed a flexible tool that could support the breadth of reviews that we undertook. We were not the only people who needed such a tool, and as requests came in for other people to use the software, we developed what is now the EPPI-Reviewer service. The current version of EPPI-Reviewer (version 4) first went online in 2010, and we have extended its functionality substantially since. (For those of you interested in history, EPPI-Reviewer began as a desktop application in 1993 called ‘EPIC’ and first went online as a service to people outside the EPPI-Centre in the late 1990s.)

So, EPPI-Reviewer is designed from the bottom up to be a flexible research tool that supports a range of methodologies – and also methodological innovation. The development team is in close contact with colleagues conducting reviews (in the same small building as many) so we have been able to extend and modify the software in response to reviewer need. For example, it contains the widest range of automation functionality of any systematic review tool (supporting ‘priority screening’ for efficient citation screening, with three high performing study-type classifiers, the ability to ‘make your own’ machine learning classifier, and text clustering tools); it supports meta-analysis, meta-regression and network meta-analysis using packages in the ‘R’ statistical environment, as well as ‘line-by-line coding’ for qualitative evidence synthesis. Packing such a large range of functions into a single application is challenging of course, and we have prioritised functionality over providing a smooth ‘workflow’ model, where reviewers are expected to follow a specific path.

Current technology challenges

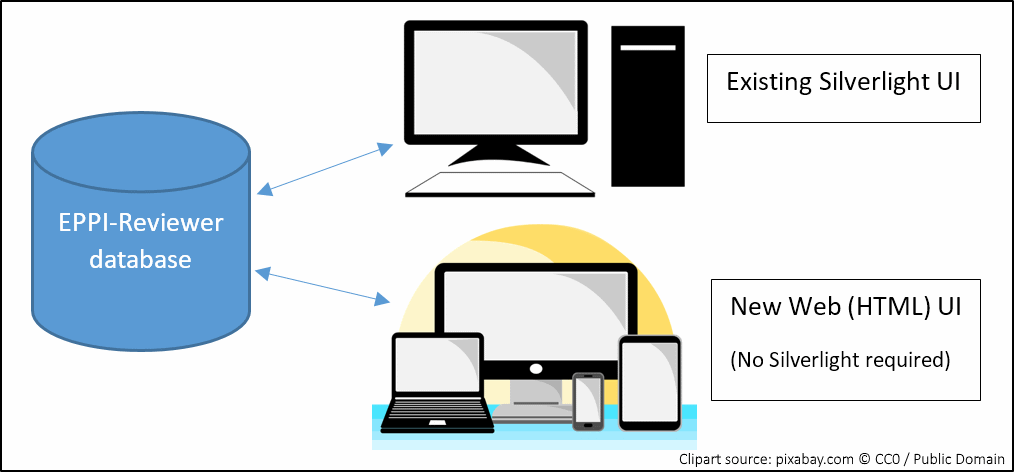

EPPI-Reviewer version 4 runs in the Microsoft Silverlight browser plugin. This provided a ‘desktop-like’ application experience in a web browser across the Windows and OSX operating systems. The demise of such plugins and the rise of diverse mobile devices has led to a rapid development effort. We launched the first version of a new user interface last month: a tool which mimics the ‘coding only’ functionality that you may be familiar with. This enables users to do screening and data extraction in any web browser without the Silverlight plugin.

Currently, it is necessary to do the review setup and analysis phases using the Silverlight version (for practical guidance re Silverlight, please see here), so we are now extending our new user interface to support these processes too – and hope to have most of the essentials covered by Christmas. The figure below shows how, in the meantime, we will have two different user interfaces interacting with the same database. This means that you can log in using either user interface and work on exactly the same review.

New and upcoming developments

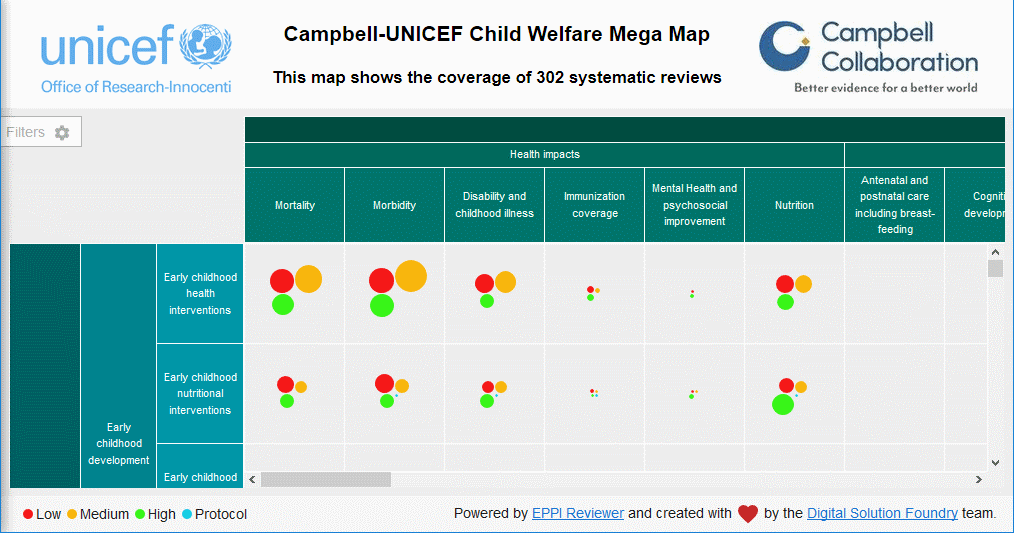

We have partnered with the Campbell Collaboration to produce a user interface – based on the EPPI-Reviewer database – for ‘mapping’ research activity. These maps provide a user-friendly way of presenting the extent and nature of research in a broad domain. The columns and rows in the example below are defined in EPPI-Reviewer as ‘codes’ and the circles indicate the quantity and quality of evidence in each cell.

We are also designing some new data services as application programming interfaces (APIs) that a range of different applications can use. These data services are built on large sets of data and incorporate the latest automation tools to enable users to locate relevant research quickly. These services are looking forward to a world of ‘living’ systematic reviews (which we have written about elsewhere) where we keep reviews updated with new evidence as soon as it becomes available. We are planning to extend our support for ‘maps’ to include creating automatically updated maps in due course. Dealing with large amounts of data poses significant technical challenges, but being researchers, we are also busy evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of underpinning reviews with new data services. When we make these services available, we will also need to publish robust evaluations to support their use.

What about EPPI-Reviewer Version 5?

As some of you may know, we have been partnering with NICE to develop a new version of EPPI-Reviewer. The software is now being rolled out internally at NICE, but is currently more attuned to NICE’s needs than other external users, so we are concentrating our immediate development effort on giving our users an alternative entry point into the existing EPPI-Reviewer database. This strategy also gives users a seamless migration from one user interface into the other.

Conclusion

As this brief post indicates, this is a busy and exciting period of development here at the EPPI-Centre. We are always busy making progress on multiple fronts, so to make sure we can rapidly adapt our plans as and when we discover what works best for us and our whole community. As always, this means that feedback received via the forums and email is highly appreciated. As we move forward we will post further updates. Please do get in touch if you have any questions or feedback.

The EPPI-Reviewer Core team

The EPPI-Reviewer core team is small, agile and tight. The main members are listed below, in order of appearance. This list does not include the numerous people in the EPPI-Centre and beyond, who on occasion provide suggestions, advice and/or specialised contributions – this other list would be much, much longer!

James Thomas is the team leader and scientific director – he wrote the very first version(s) of EPPI-Reviewer and produces the prototypes of most new/innovative features of EPPI-Reviewer. James also leads the methodological-evaluation efforts that normally precede making any new methodology available to the larger community.

Jeff Brunton oversees user support and licensing. He is the lead developer for the Account Manager, the Web-Databases applications, RIS export and directed the development of the new mapping tool – along with James, he wrote EPPI-Reviewer version 3. He is also responsible for Testing and User Experience.

Sergio Graziosi spends most of his time inside the EPPI-Reviewer code. He brings James’ prototypes to production and makes sure all nuts and bolts are tightened up, while mechanisms (including systems) are well oiled. Along with Patrick, he wrote the first version of the (non-Silverlight) coding App.

Zak Ghouze provides user support and looks after our numerous systems. He is also consulting in designing the shape and feel of the new interface as well as providing invaluable insight into the minds of EPPI-Reviewer users. Along with Jeff, he is shaping the User Experience of our latest developments.

Patrick O’Driscoll writes code for all occasions. He brings fresh ideas to the team by means of new and varied experience on Web-Based front-ends as well as vast array of technologies and development methodologies. Together with Sergio, he is now busy writing the new web-based application.

|

Graziosi posted on October 02, 2018 14:03

Enthusiasm for public and patient involvement (PPI) in research is gaining momentum. But how can stakeholders be involved in a review process? What are the specific arguments and challenges for involving young people who are deemed to be ‘vulnerable’ in the research that affects them? Louca-Mai Brady and Sarah Lester reflect on the key lessons learned from holding a workshop for young people with lived experience of adverse childhood experiences in the early stages of a review.

What is the review about?

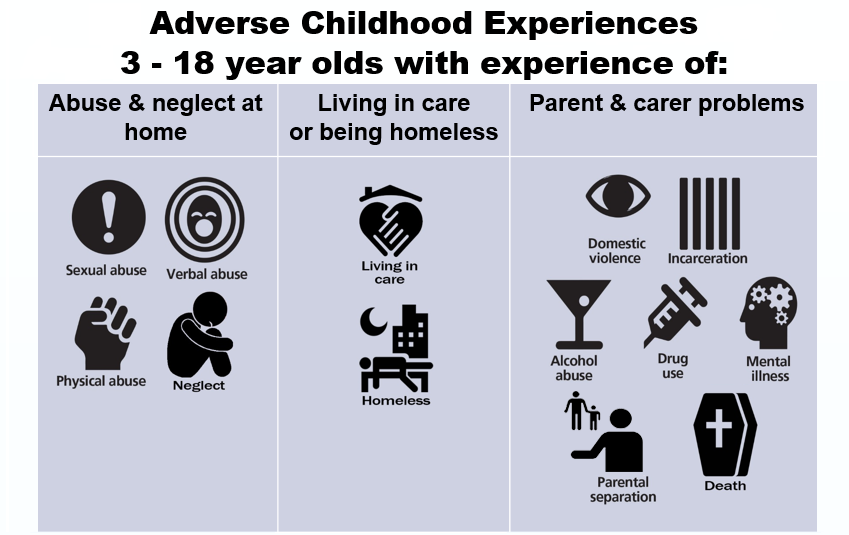

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are stressful experiences that happen during childhood or adolescence that directly harm a child or negatively affect the environment in which they live. It is estimated that almost half of adults in England have been exposed to at least one form of adversity during their childhood or adolescence. A large US study in the 1990s first popularised the term ACEs and explored the negative impact of unaddressed childhood adversity on people’s health and behaviour across the life course. More recent research suggests that at least one in three diagnosed mental health conditions in adulthood directly relate to trauma brought about by ACEs.

The alarming prevalence and consequences of ACEs are largely understood, but the Department of Health and Social Care want to know what helps improve the lives of people with experience of ACEs. We are currently conducting a review of reviews to try to answer this question as part of the Department of Health and Social Care Reviews Facility. Our definition of ACE populations is informed by the previously mentioned US study and the UCL Institute of Health Equity’s ACE review. It spans twelve distinct but interrelated populations.

| |

|

| Populations as defined for the ACEs review |

Why did we want to involve young people in the review?

The 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child established international recognition that all children have a right to have a say in decisions that affect them.

However, the voices of young people who are deemed to be ‘vulnerable’ are often absent from the literature and consequently there is the risk that they will be underrepresented in the key outputs designed to inform policy (see findings from the UN Committee on the Rights of Child, UNRC, 2016, p.6-7). Involvement should also lead to research, and ultimately services, that better reflect young people’s priorities and concerns (Brady et al., 2018). With this in mind, we wanted to consult with young people with lived experience of ACEs in order to keep our review grounded in their experience and perspectives.

We decided to hold a workshop during the early stages of the review process to help us to verify whether the evidence we were finding was relevant to the current UK context and young people’s lived experience, and to explore how we might involve young people later on in the review if possible, or in future research.

While involving children and young people in research is still an emerging field (Parsons et al. 2018), the work discussed here builds on previous research on involving young people in systematic reviews (Jamal et al., 2014, Oliver et al., 2015).

How did we involve young people?

We began by identifying and contacting organisations who worked with young people affected by ACEs, as well as researchers and topic experts. We aimed to recruit between five and ten young people, knowing from previous experience that this was an optimum number to encourage everyone to talk. On the day, seven young people attended, most supported to do so by a mentor from the National Children’s Bureau.

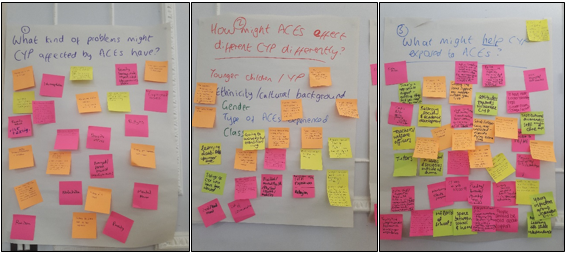

At the workshop we spoke to the young people about our project. It was too early to relay concrete findings, but we told them about some emerging patterns in the research. As well as covering specific topics such as counselling and therapy (which dominates the effectiveness research), and discussing the kinds of outcomes they valued, the majority of the discussion took place around three main questions:

- What kinds of problems might children and young people affected by ACEs have?

- How might ACEs affect people differently (i.e depending on their gender, background, age)?

- What might help children and young people who are exposed to ACEs?

Our young advisors were very forthcoming in their responses to these broad questions as it provided a platform for everyone to contribute. In our original itinerary, we had allowed just ten minutes per question (out of a three-hour session) but we found that this activity was so fruitful and it provided such fertile ground for relevant discussions that we expanded the time allocation for this section. It was clear that the young people we consulted were already research literate and eager to contribute more. We thus discovered that allowing the group to explore these question was a better use of their time than talking through lots of detailed slides on concepts they were already familiar with.

Key Learning Points

A thorough ethics application, co-creating ground rules, encouraging questions, and taking time to go through the consent form, were all essential to creating an atmosphere of mutual respect.

Being flexible and attentive to the individual preferences within the group maximised the usefulness of the workshop. Some young people were apprehensive about writing things down, preferring to talk out loud, whereas others found it easier to write their responses down on post it notes. We used a mixture of written and verbal, group and individual work in order to accommodate these various needs.

Being well prepared and knowing the material well helped us to move fluidly through the session.

We provided an information pack for the young people which we referred to throughout the session. It helped to give a sense of reassurance that the conversation could continue after the workshop and allowed more latitude for those working at different paces.

This echoes previous work by Dr Brady on involving young people with lived experience of substance misuse services: young people valued being able to use difficult personal experiences to create positive change, but doing so safely required being sensitive to individual circumstances and providing opportunities for young people who want to be involved to do so in ways that work for them (Brady et al., 2018).

Managing disclosure was also an important learning point. We explained to the young people early in the process that, although they were at the workshop because of their lived experience of ACEs, they did not need to share any personal details. However, several chose to do so, and this needed to be managed carefully to create a safe and comfortable space for everyone involved. Some of the young people who attended were also still going through difficult experiences and one needed time out because she was finding participation difficult. She left the session to sit in a nearby quiet room with the mentor who had accompanied her; and we made it clear she did not have to stay. But she chose to do so and re-joined the group for another section when she was ready. So some of our learning was around the need to expect the unexpected and be flexible in response to individual needs, particularly in this case when we were working with young people who had experienced, and in some cases were still living through, very difficult experiences.

How the workshop will inform the review

Two unifying themes of the discussion were the importance of the role of schools (even in regards to extended absence) and the need for support with practical life skills. The young people discussed how attitudes of teachers, institutional (in)flexibility, and (lack of) support at major transition points had been key barriers or facilitators to helping them feel supported through ACE trauma.

We are currently analysing primary qualitative UK studies in light of the themes arising from the workshop, with particular emphasis on the kinds of outcomes young people deemed to be important and the kinds of support that they highlighted which would help them to thrive.

The findings will be relayed to the Department of Health and Social Care and point to the need for them to work more closely with the Department of Education in their policy response to ACEs.

This is particularly relevant as the 2017 Green Paper sets out a vision to place schools at the foreground of mental health provision for children and young people (albeit by 2025).

Next Steps

As we near the final stages of the review, we are keen to re-engage with young people to verify the relevance of our findings across the different ACE populations and to the current UK context. There is also strong potential for further consultation with young people on the findings of the qualitative strand of the review, and for stakeholder events also including academics, practitioners and third sector organisations in order to reflect on or possibly to help disseminate findings.

About the authors

Dr. Louca-Mai Brady is an independent research consultant and a Research Associate at Kingston University and St George’s Joint Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education. Her research interests include children and young people’s involvement in health and social care research, policy and services and research with children and young people who are ‘less frequently heard’.

Sarah Lester is a Research Officer at EPPI-Centre. She is interested in conducting systematic reviews in the areas of mental health and social care and involving stakeholders in research processes.

This research is funded by the NIHR Policy Research Programme. Views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Bibliography

Allen, M., and Donkin, A. The impact of adverse experiences in the home on the health of children and young people, and inequalities in prevalence and effects. London: Institute of Health Equity: University College London, 2015.

Bellis, M., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., et al. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Medicine. 2014; 12, 72. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1741-7015-12-72

Brady, L., Templeton, L., Toner, P. et al. Involving young people in drug and alcohol research. Drugs and Alcohol Today 2018; 18 (1): 28-38. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-08-2017-0039

CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Violence Prevention: ACE Study. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/about.html (accessed 19.07.18)

Jamal, F., Langford, R., Daniels, P., et al. Consulting with young people to inform systematic reviews: an example from a review on the effects of schools on health. Health Expectations. 2014; 18 3225-3235. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12312

Kessler, R., McLaughlin K., Green J., et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010; 197(5): 378-385. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499

Oliver, K., Rees, R., Brady, L., et al. Broadening public participation in systematic reviews: a case example involving young people in two configurative reviews. Research Synthesis Methods. 2015; 6(2):206-217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1145

Parsons, S., Thomson, W., Cresswell, K. et al. What do young people with rheumatic conditions in the UK think about research involvement? A qualitative study. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2018; 16 (35). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0251-z

|

Graziosi posted on November 15, 2017 11:53

Dylan Kneale and Antonio Rojas-García reflect on recent work exploring the use of evidence in local public health decision-making. In new climates of public health decision-making, where the local salience of research evidence becomes an even more important determinant of its use, they question how much research is being wasted because it is not generalisable in local settings.

Our review on evidence use in local public health decision-making cast a spotlight on patterns and drivers of evidence use in England[1]. Locality was the recurring theme running throughout the review: evidence was prioritised where its salience to the local area was easily identified. Local salience included whether the evidence was transferable to the characteristics of the population, the epidemiological context, whether the proposed action was feasible (including economically feasible), but also included the political salience of the evidence.

To some, particularly those working in public health decision-making, these findings may feel all too familiar. The shift of decision-making to local government control in 2013 has served to increase the (local) politicisation of public health, which has consequent impacts on the way in which public health challenges are framed, the proposed actions to tackle these challenges, and the role of evidence in this new culture of decision-making. But these findings help to reinforce other lessons for generators evidence, because in many ways the review highlighted a thriving evidence use culture in local public health, but one that has a ‘make-do and mend’ feel about it.

Locality emerged as a key determinant of evidence use, but one where generators of evidence have only loosely engaged. There are likely good reasons for this, with research funders and publishers encouraging researchers to produce evidence that is relevant to audiences worldwide. However, this status quo means that in many ways, evidence generators may be guilty of adopting something akin to an ‘information deficit model’ around the use of research evidence – which inherently assumes that there is an information gap that can be plugged by ever more peer-reviewed research or systematic reviews that reflect ‘global’ findings[2]. This perspective overlooks epistemological issues around whether such knowledge is applicable, transferable, or otherwise relevant and useful in the context of local decision-making. It also assumes that decision-making is an event, rather than a cumulative learning process where outcomes are evaluated in different ways by different stakeholders; this perspective was reinforced in our own review by a paucity of studies that engaged with the nitty-gritty of public health decision-making processes.