What is the review about?

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are stressful experiences that happen during childhood or adolescence that directly harm a child or negatively affect the environment in which they live. It is estimated that almost half of adults in England have been exposed to at least one form of adversity during their childhood or adolescence. A large US study in the 1990s first popularised the term ACEs and explored the negative impact of unaddressed childhood adversity on people’s health and behaviour across the life course. More recent research suggests that at least one in three diagnosed mental health conditions in adulthood directly relate to trauma brought about by ACEs.

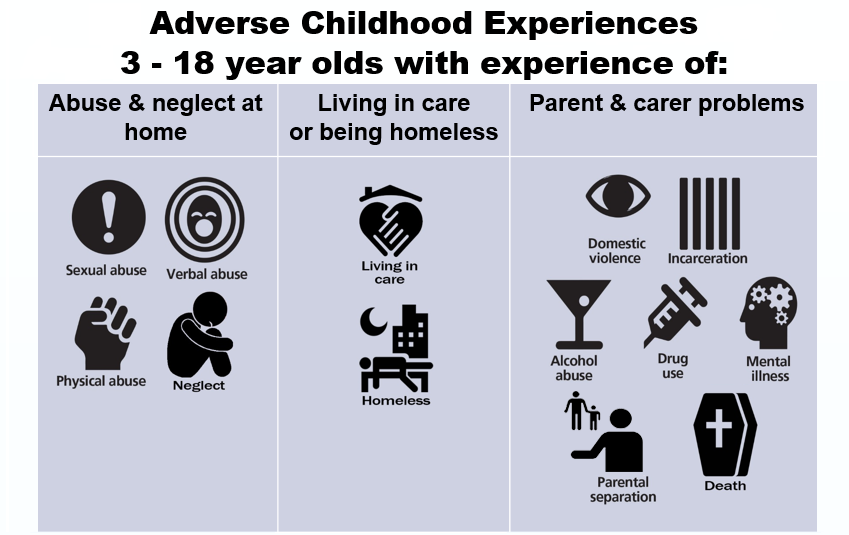

The alarming prevalence and consequences of ACEs are largely understood, but the Department of Health and Social Care want to know what helps improve the lives of people with experience of ACEs. We are currently conducting a review of reviews to try to answer this question as part of the Department of Health and Social Care Reviews Facility. Our definition of ACE populations is informed by the previously mentioned US study and the UCL Institute of Health Equity’s ACE review. It spans twelve distinct but interrelated populations.

| |

|

| Populations as defined for the ACEs review |

Why did we want to involve young people in the review?

The 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child established international recognition that all children have a right to have a say in decisions that affect them.

However, the voices of young people who are deemed to be ‘vulnerable’ are often absent from the literature and consequently there is the risk that they will be underrepresented in the key outputs designed to inform policy (see findings from the UN Committee on the Rights of Child, UNRC, 2016, p.6-7). Involvement should also lead to research, and ultimately services, that better reflect young people’s priorities and concerns (Brady et al., 2018). With this in mind, we wanted to consult with young people with lived experience of ACEs in order to keep our review grounded in their experience and perspectives.

We decided to hold a workshop during the early stages of the review process to help us to verify whether the evidence we were finding was relevant to the current UK context and young people’s lived experience, and to explore how we might involve young people later on in the review if possible, or in future research.

While involving children and young people in research is still an emerging field (Parsons et al. 2018), the work discussed here builds on previous research on involving young people in systematic reviews (Jamal et al., 2014, Oliver et al., 2015).

How did we involve young people?

We began by identifying and contacting organisations who worked with young people affected by ACEs, as well as researchers and topic experts. We aimed to recruit between five and ten young people, knowing from previous experience that this was an optimum number to encourage everyone to talk. On the day, seven young people attended, most supported to do so by a mentor from the National Children’s Bureau.

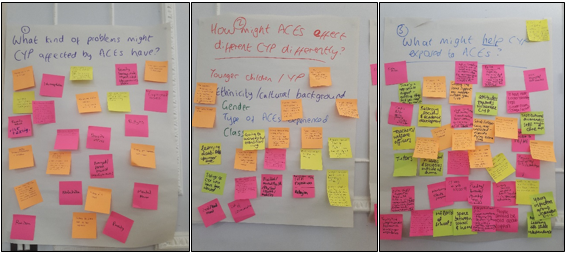

At the workshop we spoke to the young people about our project. It was too early to relay concrete findings, but we told them about some emerging patterns in the research. As well as covering specific topics such as counselling and therapy (which dominates the effectiveness research), and discussing the kinds of outcomes they valued, the majority of the discussion took place around three main questions:

- What kinds of problems might children and young people affected by ACEs have?

- How might ACEs affect people differently (i.e depending on their gender, background, age)?

- What might help children and young people who are exposed to ACEs?

Our young advisors were very forthcoming in their responses to these broad questions as it provided a platform for everyone to contribute. In our original itinerary, we had allowed just ten minutes per question (out of a three-hour session) but we found that this activity was so fruitful and it provided such fertile ground for relevant discussions that we expanded the time allocation for this section. It was clear that the young people we consulted were already research literate and eager to contribute more. We thus discovered that allowing the group to explore these question was a better use of their time than talking through lots of detailed slides on concepts they were already familiar with.

Key Learning Points

A thorough ethics application, co-creating ground rules, encouraging questions, and taking time to go through the consent form, were all essential to creating an atmosphere of mutual respect.

Being flexible and attentive to the individual preferences within the group maximised the usefulness of the workshop. Some young people were apprehensive about writing things down, preferring to talk out loud, whereas others found it easier to write their responses down on post it notes. We used a mixture of written and verbal, group and individual work in order to accommodate these various needs.

Being well prepared and knowing the material well helped us to move fluidly through the session.

We provided an information pack for the young people which we referred to throughout the session. It helped to give a sense of reassurance that the conversation could continue after the workshop and allowed more latitude for those working at different paces.

This echoes previous work by Dr Brady on involving young people with lived experience of substance misuse services: young people valued being able to use difficult personal experiences to create positive change, but doing so safely required being sensitive to individual circumstances and providing opportunities for young people who want to be involved to do so in ways that work for them (Brady et al., 2018).

Managing disclosure was also an important learning point. We explained to the young people early in the process that, although they were at the workshop because of their lived experience of ACEs, they did not need to share any personal details. However, several chose to do so, and this needed to be managed carefully to create a safe and comfortable space for everyone involved. Some of the young people who attended were also still going through difficult experiences and one needed time out because she was finding participation difficult. She left the session to sit in a nearby quiet room with the mentor who had accompanied her; and we made it clear she did not have to stay. But she chose to do so and re-joined the group for another section when she was ready. So some of our learning was around the need to expect the unexpected and be flexible in response to individual needs, particularly in this case when we were working with young people who had experienced, and in some cases were still living through, very difficult experiences.

How the workshop will inform the review

Two unifying themes of the discussion were the importance of the role of schools (even in regards to extended absence) and the need for support with practical life skills. The young people discussed how attitudes of teachers, institutional (in)flexibility, and (lack of) support at major transition points had been key barriers or facilitators to helping them feel supported through ACE trauma.

We are currently analysing primary qualitative UK studies in light of the themes arising from the workshop, with particular emphasis on the kinds of outcomes young people deemed to be important and the kinds of support that they highlighted which would help them to thrive.

The findings will be relayed to the Department of Health and Social Care and point to the need for them to work more closely with the Department of Education in their policy response to ACEs.

This is particularly relevant as the 2017 Green Paper sets out a vision to place schools at the foreground of mental health provision for children and young people (albeit by 2025).

Next Steps

As we near the final stages of the review, we are keen to re-engage with young people to verify the relevance of our findings across the different ACE populations and to the current UK context. There is also strong potential for further consultation with young people on the findings of the qualitative strand of the review, and for stakeholder events also including academics, practitioners and third sector organisations in order to reflect on or possibly to help disseminate findings.

About the authors

Dr. Louca-Mai Brady is an independent research consultant and a Research Associate at Kingston University and St George’s Joint Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education. Her research interests include children and young people’s involvement in health and social care research, policy and services and research with children and young people who are ‘less frequently heard’.

Sarah Lester is a Research Officer at EPPI-Centre. She is interested in conducting systematic reviews in the areas of mental health and social care and involving stakeholders in research processes.

This research is funded by the NIHR Policy Research Programme. Views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Bibliography

Allen, M., and Donkin, A. The impact of adverse experiences in the home on the health of children and young people, and inequalities in prevalence and effects. London: Institute of Health Equity: University College London, 2015.

Bellis, M., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., et al. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Medicine. 2014; 12, 72. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1741-7015-12-72

Brady, L., Templeton, L., Toner, P. et al. Involving young people in drug and alcohol research. Drugs and Alcohol Today 2018; 18 (1): 28-38. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-08-2017-0039

CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Violence Prevention: ACE Study. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/about.html (accessed 19.07.18)

Jamal, F., Langford, R., Daniels, P., et al. Consulting with young people to inform systematic reviews: an example from a review on the effects of schools on health. Health Expectations. 2014; 18 3225-3235. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12312

Kessler, R., McLaughlin K., Green J., et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010; 197(5): 378-385. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499

Oliver, K., Rees, R., Brady, L., et al. Broadening public participation in systematic reviews: a case example involving young people in two configurative reviews. Research Synthesis Methods. 2015; 6(2):206-217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1145

Parsons, S., Thomson, W., Cresswell, K. et al. What do young people with rheumatic conditions in the UK think about research involvement? A qualitative study. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2018; 16 (35). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0251-z